MEDIA & PHOTO GALLERY

Helping Preemies, Helping Parents:

Why Family Centered Care Needs to be the Norm in America’s NICUs

“One of our top priorities is to advocate for universal adoption of Family-Centered Care in NICUs nationwide. As the name implies, this care model revolves around parents being included as a critical part of their baby’s care team. We believe parents should be at the heart of the decision-making process, regardless of their culture, socio-economic background, or education level. We also believe parents should be given ample opportunities to physically and psychologically bond with their child.”

Wishing Flower Walk 2024 Photo Gallery

Photo Credit: R.A.W. Image Photography

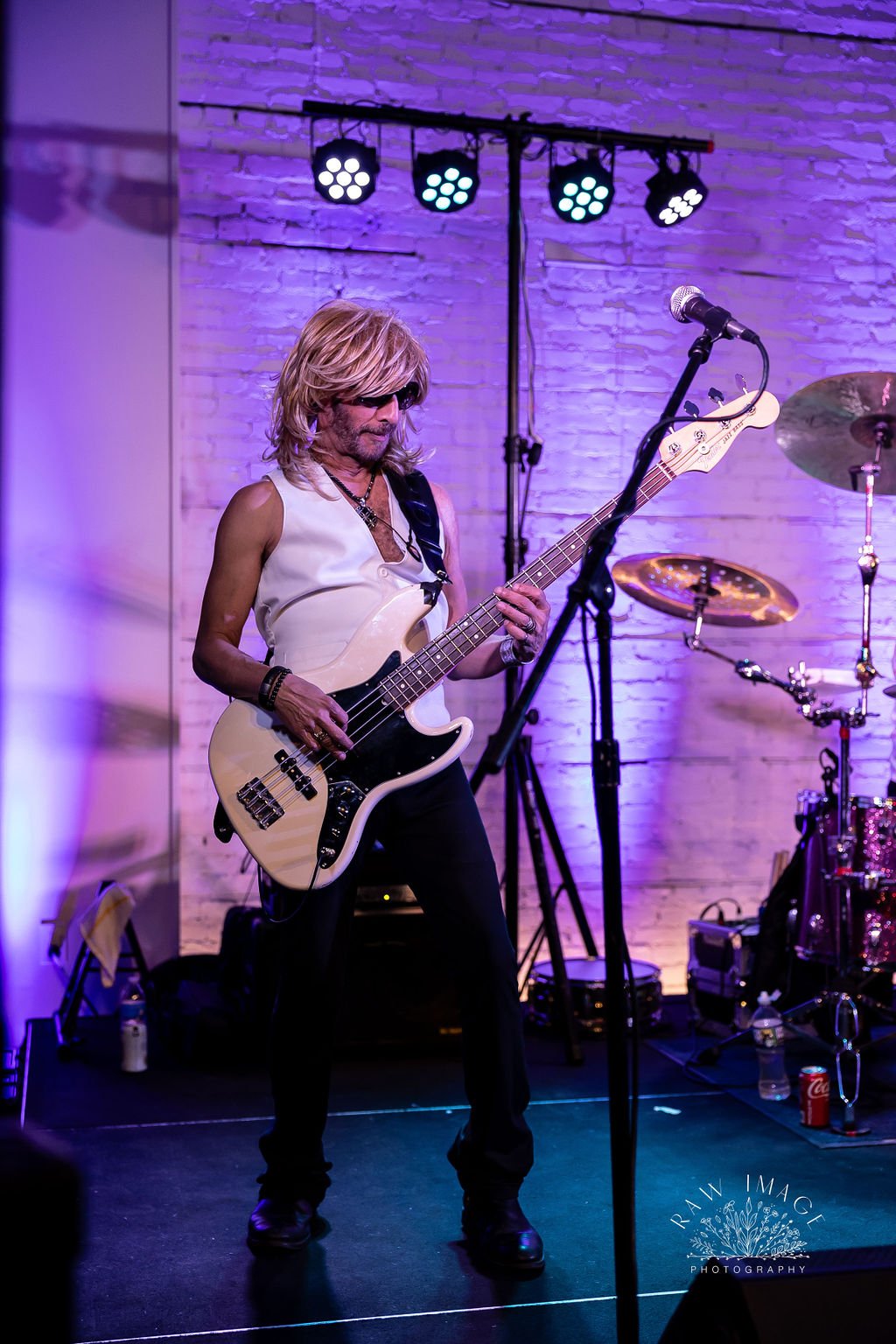

Night for Babies 2024 Photo Gallery

Photo Credit: R.A.W. Image Photography

Wishing Flower Walk 2023 Photo Gallery

Photo Credits: Spotted Lark Studio

download code: 5779

CLEAN JUICE AND NICOLE COMBS NEW COLLABORATION BENEFITS CLEVELAND-BASED NONPROFIT PROJECT NICU

“The Nicole Combs One” smoothie will be sold in over 125 Clean Juice Stores across the country and proceeds will support NICU Families during August.

Cleveland, OH – Clean Juice®, the first and only national USDA-certified organic juice bar franchise and quick service restaurant has a new collaboration. Not only is it delicious and healthy, but it also benefits NICU families across the country.

The fast-growing company announced today that their new brand ambassador, Nicole Combs, wife of Country Music Star Luke Combs and influencer, has selected Project NICU to receive $1 from each “The Nicole Combs One” smoothie for the month of August. Project NICU is a national nonprofit that raises awareness, financial support, and peer assistance for families with medically fragile infants in the neonatal intensive care unit.

“We were beyond honored to be selected by Nicole Combs and Clean Juice for this unique opportunity,” said Pam Frasco, Project NICU Founder. “It’s companies like Clean Juice, and people like Nicole Combs that can really make a difference in growing organizations like Project NICU. The need for support continues to rise, and we need all the awareness we can get so we can continue to support these families who so desperately need us.”

Based in Cleveland, Project NICU has grown to impact over 50,000 NICU families across the country through care packages, free mental health counseling, family assistance funding, peer support groups, and more.

Charitable giving continues to be important to Clean Juice, with this being the 7th campaign that has an influencer charitable tie.

At its 125 stores operating nationwide, Clean Juice will donate $1 for every “The Nicole Combs One” sold between August 1-30, 2023. The smoothie is a delicious mix of pineapple, banana, mango, strawberry, honey, protein, almond milk, and shredded coconut.

The campaign comes at a meaningful time for the NICU Community as it leads directly into September, which is NICU Awareness Month. Even though most parents don’t anticipate their baby will need medical assistance, 1 out of every 10 babies born in the United States will require NICU Care.

“We’d love to thank Nicole and Clean Juice for this collaboration, for providing the opportunity to support these families through this campaign and for continuing to use their platforms to make a difference,” said Frasco. “Our community is so grateful!”

Night for Babies 2023 Photo Gallery

Photo Credits: R.A.W. Image Photography

Rosie’s Story & Project NICU Impact

Project NICU receives grant from 100 Women Strong Ohio.

On Monday, March 1st, Project NICU participated in The First Giving event for 100 Women Strong Ohio.

Project NICU was one of three organizations who were awarded the opportunity to present to the members of 100 Women Strong to be considered for a grant as a part of one of their annual giving events.

The organization received a $5,000 contribution for the Family Assistance Fund efforts! Thank you to 100 Women Strong Ohio for believing and supporting our mission.

Featured in The Atlantic

Omicron Revived a Heartbreaking Pandemic Measure in NICUs

With cases rising, more parents were having to isolate from their vulnerable newborns.

Ryan McAdams, a neonatologist in Madison, Wisconsin, had a complex case to handle: A tiny newborn with a heart defect needed surgery. The baby had been struggling to feed, so doctors planned to insert a gastrostomy tube directly into the stomach to assist in supplementary feeding. The baby’s mother was around all the time to care for the infant, until she tested positive for COVID-19 and wasn’t allowed to be in the hospital.

The baby wasn’t feeding as well without the mom there, McAdams says. When the mom’s isolation period officially ended, at midnight before the scheduled procedure, she rushed back to the hospital. She told McAdams the agony she had experienced at home, sobbing as she watched the cribside camera set up to see her baby. “She just kept saying, ‘I wanted to be there,’” he says. “It was heartbreaking.”

As a part of the hospital where babies are sent when they are very sick—perhaps because they have trouble breathing after birth, or because they were born far earlier than expected—the NICU has a special role. Patients sometimes stay for months, cared for by nurses and parents who must inevitably take breaks, coming and going from this isolated world. And in that shuffle, Omicron found openings. As case rates rose, caring for babies in the NICU became more complex, and families struggled to keep up with changing policies.

No one ever plans on spending time in a NICU, but one in 10 babies ends up there, says Rachel Fleishman, a neonatologist in Philadelphia. Most commonly, babies head to the NICU because their transition from the womb to the world outside did not go well, even after a full term of gestation, Fleishman says. Preterm babies, as small as your hand, as light as a can of soda, might need longer stays. The babies are attached to a maze of machines and wires, and tubes in their mouth. “You’re the parent, but you’re also an observer, and you can’t fix things,” McAdams says. “It’s a really stressful, formidable environment that you’re thrown into.”

It has never been harder to be a NICU parent than now, says Rochelle DeOliveira, the director of peer support at the nonprofit Project NICU, whose son spent 97 days in the NICU. “The concerns NICU parents have always faced—sickness, visitors, hand-washing, isolation—have been hallmark aspects of the journey long before this pandemic,” she told me. But now they have become even more overwhelming and controlled.

Read: The coronavirus will surprise us again

She says the project is still hearing stories of parents who are not permitted to remove their masks or gloves when holding their babies; restrictions, in some hospitals, are still so stringent that grandparents have never been permitted to see their grandchildren. Meals in the family lounges, lactation and other support groups, and additional opportunities to connect with other parents in the NICU have been eliminated too, DeOliveira said.

Parents might live like this for months—some babies stay in the NICU that long. The goal for most of that time is simply to keep the babies alive until they’re strong enough to go home, McAdams says. “We have these fragile little babies who are like these little warriors, you know, fighting for their lives and have all these struggles against them.”

Until recently, COVID was not usually one of those struggles. “It was pretty rare to have a baby with COVID, let alone a baby that was sick with COVID,” McAdams says. That situation sometimes made him feel guilty—he was caring for all these babies, while his colleagues were managing an onslaught of death and serious illness in adults in the next wing over. The mood could grow ominous, Fleishman says, hearing alarms and codes go off several times a day in the adult ICU.

All of that has changed with the recent Omicron surge. Now the NICU where McAdams works is seeing more babies testing positive, more symptomatic babies, and many more parents with COVID. “We’re back to wearing not only surgical masks, but N95 masks and eye protection.”

The hardest part of the surge has been separating parents from babies after a parent tests positive for the coronavirus, Fleishman told me. She has seen parents who were essential workers separated from their infants, aching for their caramel smell and velvety skin, and mothers who risked losing their milk supply and pumped with such dedication that their nipples bled, asking her: “When will I get my baby back?” “That separation is really heart-wrenching for us as physicians; it’s very challenging for families, for the nurses as well.” She says she ends up calling the families often with positive updates on the baby, and they can also monitor through a cribside webcam.

But none of that makes up for not being there, for the mother or the baby.

Caregivers and infants are really a dyad—their outcomes and health play into each other’s, Clayton Shuman, a maternal-infant-health researcher at the University of Michigan, told me. When an infant in the NICU is ill, that illness affects the parent’s mental health. NICUs tend to focus on this pair, in supporting family-centered care through breastfeeding and skin-to-skin contact. But during the pandemic, infection prevention has taken over. And it makes sense: Neonates are especially vulnerable to infections.

Read: Why a three-dose vaccine for kids might actually work out

Shuman has been studying families with babies in the NICU during the pandemic, and the biggest way that the NICU has changed, he says, is a shifting ground of visitation policies. Many parents describe updated visitation policies where they have to choose prescheduled slots in which to spend limited windows of time with their baby, so as not to overlap with other parents, DeOliveira, of Project NICU, said. In one study, conducted in 2020, 46 percent of NICU parents said that only one person was allowed to visit at a time, and Shuman says his data show 67 percent of the parents reported more than one change to a policy during their child’s stay in the hospital. That makes caring for a sick baby incredibly challenging. Visitation restrictions disrupted parents’ plans to breastfeed, which can be helpful to vulnerable infants, Shuman said.

Shuman’s research fund that the parents of NICU babies were experiencing unusual levels of distress, on top of their decreasing likelihood of breastfeeding. This situation led the National Association of Neonatal Nurses to publish position statements about the role of parents as essential caregivers to their infants—not just as future caretakers but as team members in the NICU.

Policies that keep COVID-positive parents separated from their babies vary by hospital, and may have to do with factors outside doctors’ control. Some NICUs keep multiple patients in the same room; others have single-patient rooms, which allow more protection. When babies in the NICU do come down with COVID, it complicates their other medical issues—getting the coronavirus generally adds a week or two onto their hospital stay, McAdams says. And the long-term issues are still unknown for newborns: that is, whether COVID in infancy has any lingering impacts, such as brain fog, heart issues, problems with smell or taste. “A baby can’t tell you any of that stuff. There are a lot of question marks I think that will need to be studied,” he said.

At the same time, some research shows that separation from parents can be connected to babies’ failure to thrive, and could affect cognitive development, Shuman pointed out. “The NICU is that unique time when that connection is broken,” he said. “If a mom is still recovering and the baby is removed, the restrictions during COVID lead to prolonged separation of mother and infant.” In other words, the separation itself could be its own risk.

One strange silver lining that Shuman found in his research: Although having a baby during COVID increased the odds that a mother would be diagnosed with postpartum PTSD, having a baby in the NICU was sometimes protective against this type of stress, paradoxically. He thinks that’s because, in the NICU, parents had support. “We think that exposure to the nurses was somewhat protective, because they were able to provide support and consistency,” he told me. “Those who did not have a NICU baby, they didn’t have visitors, and they were overwhelmed.”

That support can, in some ways, extend to a parent’s COVID diagnosis. McAdams was handling a preterm baby who wasn’t feeding well—the baby’s mother had been in the NICU for days when she tested positive for COVID. She called McAdams and told him she wanted to take the baby home.

The baby wasn’t quite ready to go home, he told her; it needed a few more days in the hospital to really make sure that the feeding was going fine. McAdams also ordered a COVID test for the baby—and it came back positive. Fortunately, the baby was not symptomatic. McAdams called the mom back, and arranged for her to stay isolated in the NICU with the baby, so that they could be together and she could breastfeed. It ended up working out: The baby didn’t get ill, and was able to stay with the mother. But there were challenges, McAdams said: “If mom then gets sick in the hospital, we’re in the neonatal ICU. It’s not the adult ICU, so if mom gets sick, we really can’t take care of her—she’s not our patient.” Ultimately, their job is to do whatever is best for the baby.

The Atlantic’s COVID-19 coverage is supported by grants from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Katharine Gammon is a freelance science writer based in Santa Monica,

Katie Martin / The Atlantic; Manuel Litran / Getty; NIAID

Cleveland, Ohio, Non-Profit Awarded National Grant to Fund Perinatal Counseling Program

Pam was awarded a 2021 Nation of Neighbors℠ grant, which will allow Project NICU to launch a new counseling program. “This program will allow us to add a much-needed layer to our support approach offering direct mental health counseling to parents who have experienced a traumatic birth and NICU journey,” Pam said. “By providing scholarships, we can eliminate a barrier for families to receive the support they so desperately need.”

October 2021- Pam Frasco, Founder of Project NICU receives the Mom2.0 Iris Award: Philanthropic Work of the Year

“Nearly every form of popular art and commerce has a forum for recognizing excellent work. Nearly every industry has a means for recognizing superior achievements in its field. And we want to honor the art of modern parenthood and its new medium.

This is the Iris Awards, an annual recognition of individual achievements, collective creativity, and impactful work that comes from our community.”

Night For Babies 2020

2019 SANTA HOME TOUR

NICU Mothers Day Brunch

Project Preemie Santa Home Tour 2018

Project NICU Videos

Thanksgiving Video 2018.